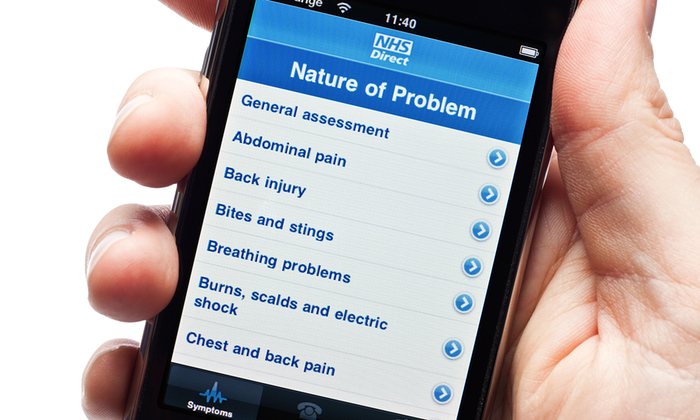

Most of the 165,000 mobile health apps available offer advice on diet and fitness but new ones are diagnosing illness and recommending treatment.

You have a fever, can’t eat and you’re barely strong enough to get out of bed. So you phone your GP surgery for an appointment, only to be told that the first one is two weeks away.

It probably sounds familiar. But could technology offer an alternative? A mobile app, Your.MD, is promising something radically different. Billed as a personal health assistant, it uses artificial intelligence (AI) to mimic, as far as possible, your consultation with a GP. If you tell Your.MD your symptoms, it will tell you what it thinks your problem might be.

This probably sounds like the flowchart that an operator will take you through when you dial 111. In fact, says chief executive Matteo Berlucchi it’s very different, because it uses Bayesian logic – a way of analysing data where every new piece of information works with the others to reach a diagnosis.

The app’s content is derived from the NHS Choices website, but the firm has also worked with doctors to crowdsource information. “Essentially, we’re taking pieces of knowledge from each doctor’s brain like puzzle pieces and putting it into one big system,” Berlucchi says. There’s one additional element: the app learns from each user consultation, enabling it to become more accurate.

Your.MD is one of a staggering 165,000 health apps available through our mobile phones, though most offer simpler advice on diet and fitness. GP and Guardian columnist Ann Robinson says fitness apps “provide useful nudges to behaviour”. But, she adds: “We still haven’t developed an app that gets the person who’s completely allergic to doing any form of exercise off the couch in the first place.”

The more useful apps, Robinson believes, are the ones that monitor complex conditions such as diabetes or the heart condition atrial fibrillation. In a trial at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, for example, patients are monitoring their oxygen levels and blood pressure and sending in results by mobile phone, where their heart specialist can see it. Apps such as these are not going to replace doctors, says Robinson, but “they will augment the diagnostic process and allow us to capture relatively rare events which have medical significance”.

But some apps hold out the promise of bypassing the NHS altogether. Like Your.MD, Babylon Health is planning to launch an AI diagnostic app. Founder Ali Parsa says AI “can play a crucial role in assisting with simpler queries to give doctors more time to focus on more complex conditions and patients who need a greater level of care”.

Berlucchi agrees: “Only an automated, computer-driven solution can help cope with the surging number of people needing help with their health.”

Perhaps, more controversially, Babylon Health also offers a subscription service that enables users to hold a phone or videophone consultation with a Babylon GP seven days a week, at short notice. While this looks like a threat to the NHS, two GP practices in Essex have partnered with Babylon Health to give patients the option to use the service as a way of reducing their own waiting times.

Julie Bretland, director and CEO of Our Mobile Health, which provides a service evaluating the quality of mobile apps, believes the best apps have the potential to reduce patient interactions with doctors: “You may get to the stage where you’re only going to physically see somebody if you need to be prodded, or have surgery. And then post-treatment, tracking and monitoring how your progress is going, or rehabilitation exercises, could be done through apps.”

However, Karen Taylor, research director at Deloitte’s centre for heath solutions, says there are a lot of issues to resolve before we get to that stage. One is quality control: consumers don’t know which apps can be trusted to provide reliable information. Some clinicians may be worried about their monopoly being undermined and concerned about their personal responsibility. “If a doctor suggests to a patient that they might want to download an app and something doesn’t go right, who would be liable?” says Taylor.

Privacy and security are also major hurdles. The European Commission, Taylor says, has found that widespread take-up of mobile health tools is being hampered by lack of confidence in security and fears about data being shared with a third party. Currently only apps that have a specific medical purpose (as opposed to simply monitoring fitness, for example) are regulated by the European Union.

So how likely is it that we’ll be staying away from GP surgeries and turning to our phones for healthcare? Robinson is sceptical. The NHS’s 111 triage service uses advanced decision-making tools but, she says: “It’s amazing how often the endpoint of that complex process is: ‘We suggest you go and see your GP on Monday’.”

This post originally appeared in The Guardian